“It’s just politics.”

This is a common enough phrase, and the usual implication of it is dismissive: if it’s just politics, it’s not about anything really important. It’s grandstanding, it’s just more sound and fury, it’s a sausage factory. At best, it’s the domain of the politicians; let them worry about it. There’s a long post in me about how the attitude behind “it’s just politics” contributes to poor participation in democracy and bad policymaking.

This is not that post.

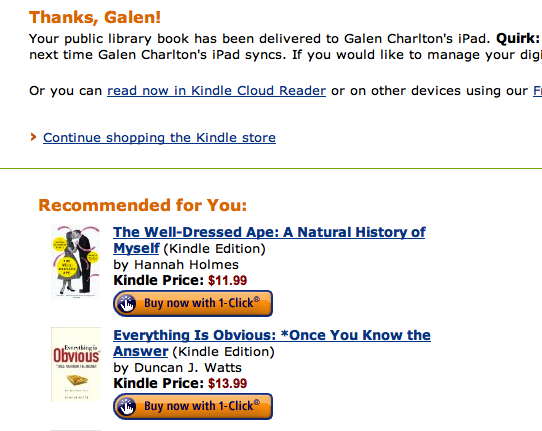

The inspiration for the post before you was somebody making a comment to more or less that effect the other day in regards to the past and ongoing controversy regarding Koha, its licensing, its trademarks, and its forks. My position on the matter should come as no surprise. If you want Koha, go to http://koha-community.org/. If you’re a librarian using it, please contribute back where you can and participate in the Koha community. If you’re a vendor supporting, implementing, or hacking it, know that it is not just yours, you should give back, obey both the letter and the spirit of the GPL, be a good community member, and don’t worry: you can do all that and still make money! Look Ma! No monopoly!

But dragging myself back on topic, one thing to clear up first: this post is not about the comment that inspired it. I am going after a generality here, not any particular throwaway comment.

What can “it’s just politics” mean when talking about a dispute concerning an open source project and its licensing? Quite a few things:

- (Re)opening this can of worms is going to derail any discussion of the software itself for weeks. This can be a very real concern: disputes about the license or the direction of the project can take years to resolve, can become very acrimonious, and frankly can be terribly boring. I, for one, personally don’t find license disputes inherently interesting, and I strongly suspect that most participants in F/OSS projects don’t either. But bitter experience has shown me that sometimes it is necessary to participate anyway and not leave it just to the language lawyers. What can make resolving disputes even more difficult is that email and IRC as communication media have weaknesses that can exacerbate conflict.

- Less talk, more code! What doesn’t get done if you’ve just spent an hour fisking the latest volley in the GPL2+ vs. AGPL3 debate? There’s an opportunity cost — that hour wasn’t spent writing some code, or testing, or proofreading the latest documentation edits. That opportunity cost can compound — if you don’t get the kudos for the results of that fisking and miss the warm feeling you get seeing a longstanding bug get closed because of your patch, you may end up disengaging.

- Can’t we all get along? It can be very unpleasant being in the middle of an important dispute. While I do think that the Koha community has come out of this stronger than ever, I also mourn the opportunities for human connection and friendships that have been permanently sundered as a result of the conflict.

- Newbie here. What is going on?!? It can be very disorienting checking out the mailing list of a F/OSS project you’re considering using only to find that everybody apparently hates each other. It can be even worse if you find yourself making an innocent statement that gets interpreted as firmly putting yourself in one camp or another. Tying this back to the previous point, is the Koha community stronger? Yes. Has it also developed a few shibboleths that cause project regulars to sometimes come down a little too hard on new members of the community? Unfortunately, yes.

- From the point of view of an external observer, it’s hard to make sense of what’s going on. It’s all too easy to lose the thread of what’s is being disputed, and the definitive histories of the war tend to come out only after the last bodies have been buried. On the other hand, particularly if you’re an external observer who has some external or self-imposed reason to make judgements about the dispute, do your research: a snap conclusion will almost certainly be the wrong one, or at least lack important nuance.

- The noise is getting in the way of figuring out if this software is useful. Fair enough — and if you’re a librarian evaluating ILSs, obviously a key part of your decision should be based on the answer to the following question: will a given ILS solve my problem, either now or in the the realistically foreseeable future. But read on, since that isn’t the only question to be answered.

The outcome of a big dispute in a F/OSS project can be positive, but there’s no question that it can be tremendously messy and painful. But just like in the realm of the elephants, donkeys, and greens, politics informs policy. And policy consequences matter. And there’s no royal road to success:

- Software doesn’t write itself. People are always involved, and unless you’ve just fired-and-forgotten some code into the wild, any F/OSS project worth thinking about involves more than just one person.

- The invisible hand is still here. The economics of a F/OSS project may not be based on cash money (though there’s a place for both money and passion), but the fundamental economic problem of resource allocation and human motivation is inescapable.

- Communities don’t build themselves, and they certainly don’t maintain themselves without effort. In the case of library-related F/OSS projects, there are special considerations: both the library profession and F/OSS hackerdom value sharing. However, there are significant differences in the ways that libraries and hackers tend to communicate and collaborate, and those differences can’t be negotiated without a lot of communication.

- Regardless of whether you fall more on the “F” side or the “OS” side of the divide in the acronym, F/OSS works for a combination of baldly pragmatic and ethical reasons. But as the very structure of the “F/OSS” acronym implies, there’s are many disagreements and differences of emphasis among F/OSS contributors and users.

What’s missing from these bullet points? The One True Path to Open Source Success. Why is it missing? Because it doesn’t exist: free software has been around long enough that there’s a good body of recommendations on how to do it well, but there’s no consensus.

And if there’s no consensus, then what? It has to be found — or created — or not found, leading to a hopefully amicable parting of the ways. But that can’t happen without discussion, conflict, and resolution. While it certainly isn’t necessary for everybody to participate in every single debate, (constructive!) engagement with the discussion can be a valuable contribution in its own right. If you can help improve how the discussion takes place, even better.

If you or your institution has a stake in the outcome, participating is part of both the duty and promise of F/OSS for libraries: owning our tools, without which our collections will just gather dust.

Put another way, politics, in its broadest and most noble meaning, can’t be avoided, even if engaging means spending some time away from the code. You may as well embrace it.

By the way, I suspect that if you did get manage to get software to write itself, you still couldn’t escape politics. I doubt that an artificial intelligence creative enough to code can be built without incorporating a sufficient degree of complexity that it would be able to avoid all moments of indecision. AI politics may well end up looking rather bizarre to humans, but they’d still be faced with the basic political problem of resolving conflict and allocating resources.